I guess I am one of those people that really enjoy this time of the year, so I had to add another post. This is a sneaky(?) second post for #FsAdvent. Ready for some more computation expressions?

In the previous post I introduced a definition and parts of a computation expression, as well as one of the simplest example.

The beauty of reality

I started looking at computation expressions because I was trying to deal with the “C#-F# design mismatch”(™) (yes I just made discovered that up) meaning that I wanted to deal in some nice ways with the fact that when I am using a C# object it will occasionally be null and other fun things. And when I started reading about solutions to that, I found that there are some well known ways to deal with that.

Sometimes the world surprises you with something amazing, could be a moon rising in the night sky, or maybe someone having a nice gesture towards another fellow human just because. Perhaps there is something to this natural ordered chaos. And with ordered chaos in mind, a great example of usage of computation expressions is error handling.

So, lets see some code

type MaybeBuilder() =

member __.Bind(maybeValue, func) =

match maybeValue with

| Some value -> func value

| None -> None

member __.Return value = Some value

let divide a b =

match b with

| 0 -> None

| _ -> Some(a / b)

let maybe = MaybeBuilder()

let divisionM a b c d =

maybe { let! x = divide a b

let! y = divide x c

let! z = divide y d

return z }

Similar to the example in the previous post, we have a builder, in this case, MaybeBuilder and the signature for this function is :

Bind:: ‘a option * (‘a -> ‘b option) -> ‘b option

Bind takes a wrapped value (‘a option) and a function that takes an 'a and returns a wrapped 'b (‘b option) and returns a wrapped 'b(‘b option). In F#, 'a option is a generic option where ‘a can be any type. You can use most generic types as wrappers.

A great explanation on why Bind signature is relevant comes from this post. Go ahead and read it. I’ll just pretend you didn’t read it try to explain it and then you will think that it might be good to go and read it :D

What happens in Bind if maybeValue has a value

- Unwrap ‘a , execute the function

- Return a wrapped value (of type ‘b option)

What happens in Bind if maybeValue is nothing

- There is

Noneso we do nothing. - Return a None (which is still of type ‘b option )

The good thing is, because we return with signature 'b option that means we can feed the result back into Bind if that is necessary.

This triple of a wrapped type, Bind and Return is called a monad, and that is cool because when you realise something is a monad, then that means you get some other stuff for free. To show you how, I’ll start talking about Monoids.

Monoids

I am sure you have heard that

A monad is a monoid in the category of endofunctors.

When I read that first I have to admit that was not terribly useful. So I went to check out Monoid, and it turns out they are pretty cool :D

A monoid needs a type and an operation and it needs to follow the following rules:

- Closure. The operation must have the following signature ‘a -> ‘a -> ‘a

- identity. There must exist an instance I of ‘a such that ‘a . I = ‘a

- Associativity. Given the same order, no matter how we associate the operations so (a . b). c = a .( b. c ) where a, b and c are instances of ‘a

examples For The Win!!

lets say we have a type Colour and an operation addColour

type Colour =

{ r : byte

g : byte

b : byte

a : byte }

let addColour c1 c2 =

{ r = c1.r + c2.r

g = c1.g + c2.g

b = c1.b + c2.b

a = c1.a + c2.a }Does this constitute a monoid?

-

Closure: the function

addColourhas the signature:val addColour : c1:Colour -> c2:Colour -> ColourIt looks like we do have closure. -

Identity. There exist a colour, black, that if you add to any other colour, the result is the same colour.

let neutral = { r = 0uy; g = 0uy; b = 0uy; a = 0uy }

let someColour = {r=44uy; g=21uy;b=99uy;a=255uy};;

do someColour = (addColour neutral someColour) |> printfn "Should be true: %A"

// This test covers just one case, we will deal with that shortly

It looks like we have an identity

- Associativity. We can add three different colours and no matter which two we add in which order, the result is the same colour.

let ``The operation is commutative`` (a : Colour, b : Colour, c : Colour) =

addColour a (addColour b c) = ( addColour (addColour a b) c)

Check.Quick ``The operation is commutative``

When we run that the result is:

` Ok, passed 100 tests. val it : unit = ()`

What happened here is that we randomly generated a, b and c to be 3 colours and we ran that test a hundred times. Verifying that in fact this pair is a monoid.

Knowing that something is a monoid can be really useful because you have certain properties that are true of monoids, for example:

- You can convert pair-wise operations to operations that apply to collections

- You can parallelise operations

- Incrementalism

For more details on monoids, please read this post.

The obvious next step now is to create monoids with computation expressions, and this is very cool because to implement them we need some of the other functions that we can use in a builder.

type MonoidBuilder ()=

member this.Zero() = neutral

member this.Combine(x, y) = addColour x y

member x.For(sequence, body) =

let combine a b = x.Combine(a, body b)

let Z = x.Zero()

Seq.fold combine Z sequence

member x.Yield (a) = a

let monoid = new MonoidBuilder()

let monoidAdd xs= monoid {

for x in xs do

yield x

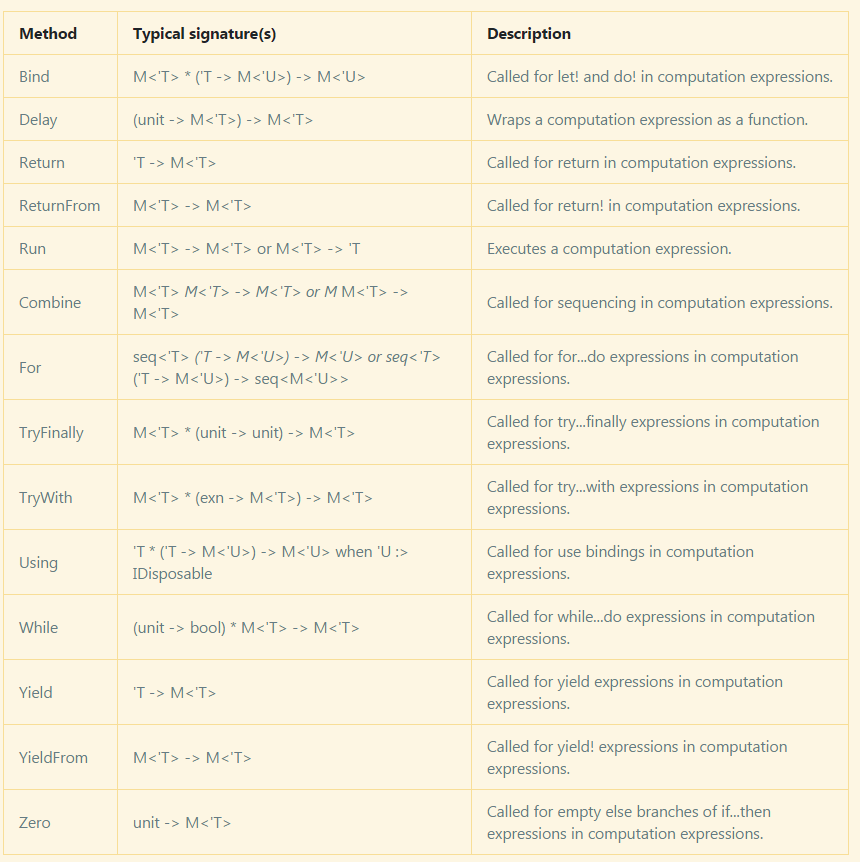

}In here we are using some new members: Zero, Yield, Combine and For. Below are all the functions that can be used on builders,

Custom Operations

type SimpleSequenceBuilder() =

member __.For (source : seq<'a>, body : 'a -> seq<'b>) =

seq { for v in source do yield! body v }

member __.Yield (item:'a) : seq<'a> = seq { yield item }

[<CustomOperation("where")>]

member __.Where (source : seq<'a>, f: 'a -> bool) : seq<'a> = Seq.filter f source

let myseq = SimpleSequenceBuilder()and you can call this

myseq {

for i in 1 .. 10 do

where (fun x -> x > 5)

}this translates to:

let b = myseq

b.Where(

b.For([1..10], fun i ->

b.Yield (i)),

fun x -> x > 5)I guess by now we are all a bit tired like these otters:

See you next time

Batmandrea

References

- Functors, Applicatives, And Monads In Pictures

- Computation expression wikibooks

- Computation Expressions (F#) msdn

- Some Details on F# Computation Expressions - D Syme 2007

- The computation expression series - F# for fun and profit

- Why Do Monads Matter?

- Where is the monad A post on FParsec about why they moved away from a monadic aproach due to performance

- The Road to Functional Programming in F# – From Imperative to Computation Expressions

- FSharpx.Extras (github repo)

- The marvels of monads - Wes Dyer